Long-term Alignment in Cryptonetworks & DAOs

by Felix Machart, July 2, 2021

Special focus: Time-lock weighted token voting

— This post also appeared on Mirror and a longer version covering DeFi case studies (Curve & Sovryn) is available here on Arweave —

One of the most difficult problems in any organization is how to balance short-term interests and long-term goals.

Both are necessary for sustainable success in provisioning goods and services, but in traditional finance (TradFi) as well as decentralized finance (DeFi) capital markets there is a growing trend towards focusing on the short-term. In TradFi, figureheads such as Warren Buffet and Jamie Dimon recognize this problem and are publicly advocating for the elimination of the focus on quarterly earnings reports. In DeFi, liquidity mining has attracted significant mercenary capital that rapidly moves wherever the highest yields are paid in the short-term.

One great quality of blockchains is that they democratize access to data. Anyone can view and verify metrics like earnings, transactions, risk and solvency in real-time. Community analysts can build upon each other’s work in open-source collaborations.

However, if quarterly reporting has led traditional firms (and their activist investors) to excessive short-term orientation, and leaders have advocated decreasing reporting frequency, where will real-time accounting lead us?

Having a clearer picture on our circumstances should enable us to make better decisions on resource allocation. On what time-frame though?

Focusing on the long-term matters

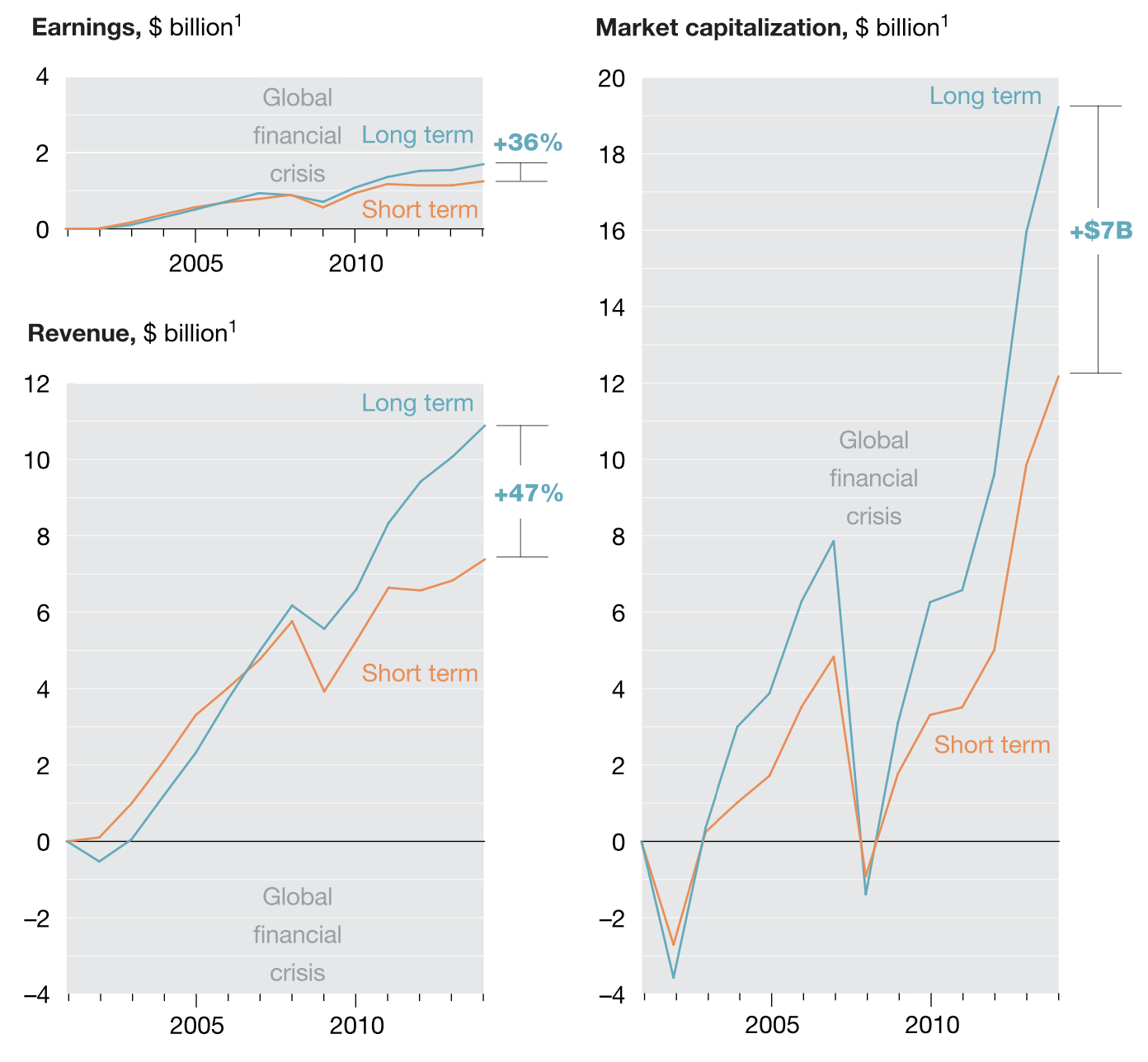

When looking at for-profit sector data, we see significantly better business metrics in long-term focused firms than their counterparts (see chart below).

Beyond financial metrics, long-term firms added nearly 12k more jobs on average than other firms from 2001 to 2015, thus contributing more to the ecosystems they operate in through financing the livelihoods of people.

As innovation is one of the strongest drivers of sustainable success, one likely explanation for the outperformance is significantly higher growth in R&D spending (8.5% vs. 3.7% per annum.).

Management researcher Jim Collins also shows in “Built to Last” that long-term oriented companies have outperformed their peers in terms of stock performance. He mainly argues that such visionary companies have cult-like cultures and preserve their core that goes beyond making profits (mission/ideology/values), while at the same time stimulating progress and innovation.

Former McKinsey boss Dominic Barton and Mark Wiseman (CEO of the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board) make the case that mainly pressure from financial markets led to a detrimental focus on short-term performance. They note that avoiding such pressure is one reason why private equity firms buy publicly traded companies to take them private. The result is that investing in private equity rather than comparable public companies yields long-term annual returns that are 1.5%-2% higher. Reversing this detrimental trend in public markets, they argue, depends on the leadership of major asset owners and their active involvement in governance.

If history in the context of traditional companies has shown that optimizing for the long-run creates more wealth, it is likely that the same holds true for cryptonetworks. One could argue that long-term alignment in cryptonetworks is even more important given that they are meant to outlast their initial founding teams and communities (even though that is also true for “visionary” companies as Jim Collins defines them).

How do we design incentives for optimizing long-term performance in cryptonetworks?

Cryptonetworks often issue liquid tokens at inception that allow stakeholders to easily on-board and participate in governance. Traditional tech companies on the other hand deliberately remain private for longer.

What if the pressures of a liquid market for governance tokens in cryptonetworks are detrimental to long-term success, such as what has been observed with traditional companies? If so, can we leverage programmable illiquidity (lock-ups) to strategically align long-term incentives?

To analyze this question we need to first examine the typical stakeholder-relationships and control structures in a cryptonetwork.

Spectrum of stakeholder-relationships in cryptonetworks/DAOs

In principle, any organizational structure can be implemented on a blockchain so there is a broad spectrum of what is considered a decentralized (autonomous) organization (DO/DAO, see our prev. post and paper).

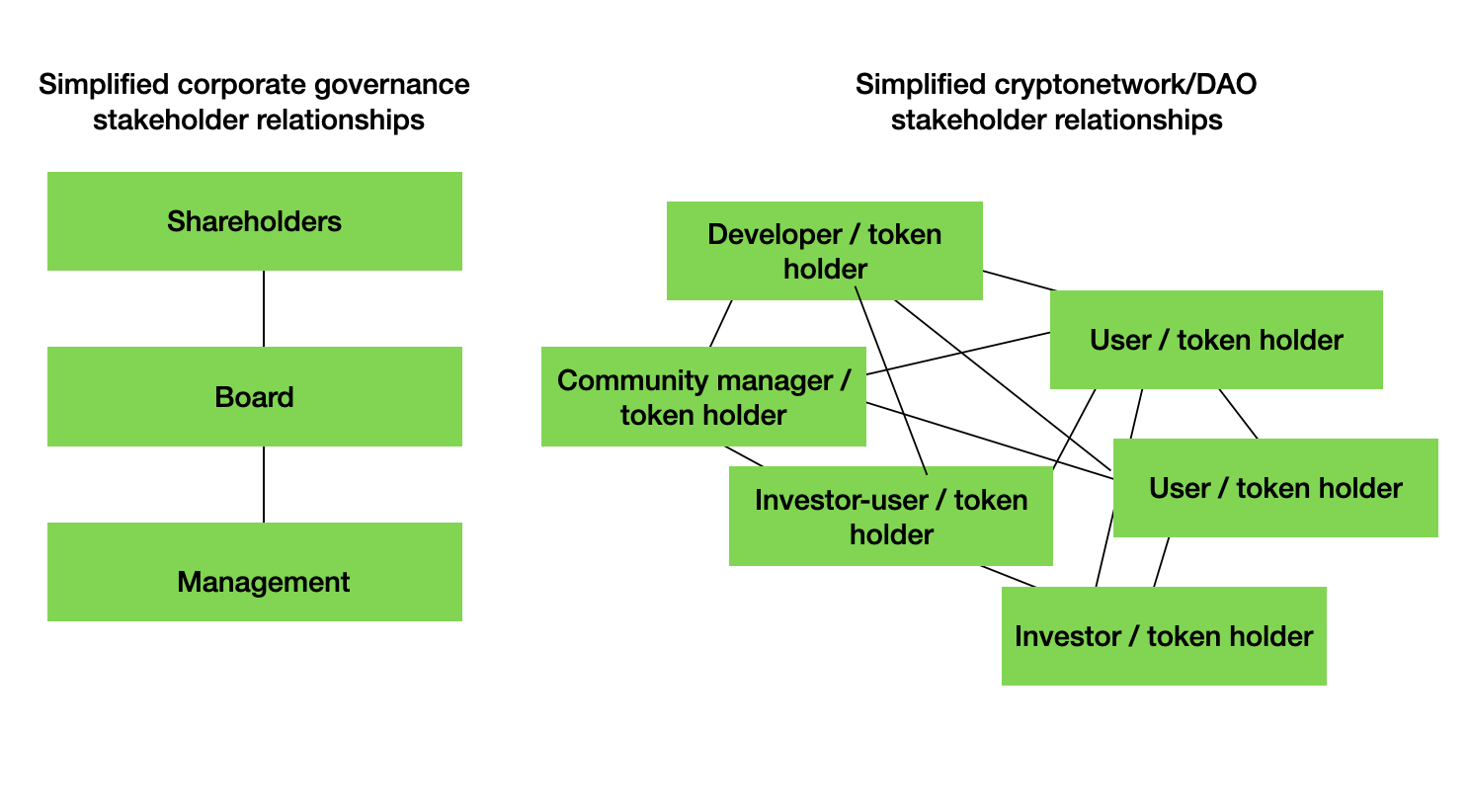

In the idealized form of a cryptonetwork or DAO, stakeholder relationships are more akin to peer-to-peer (p2p) networks or a cooperative, i.e. without any particular person, group or entity in control. (see the right side of the chart below).

Usually, however, there is a founding team that acts as a de-facto executive body driving development. Though, in many cases founding teams will need to access further funding from a project’s treasury by token-holder vote, at which point they might need to compete with alternative teams for resources.

On the other end of the spectrum is the archetypical traditional corporation in which shareholders elect a board which then appoints management to execute the company’s strategy.

Ideally, there is a wide distribution of ownership which is one angle of decentralization (often of native governance tokens). Initially, a core group of founders/developers will gather an early community and, over time, more and more stakeholders join to contribute towards the vision of the project. As a network grows and gets more diverse, so should token ownership (see also progressive decentralization).

In cryptonetworks and DAOs, ownership and decision making authority is often distributed more widely and roles overlap to a larger extent than in a corporate governance setting. However, unclear separation of roles can in practice lead to conflict and inefficient use of time/resources.

As a result, when analyzing incentive and governance structures, one needs to account for the fact that community members and token-holders are both governors (principals) as well as the governed (agents). Increasingly we see representation happening and considered advisable (token-holders often delegate their votes to protocol politicians in a flexible fashion), which again introduces classic principal-agent dynamics.

Going forward, organization designs in the crypto space might move more towards appointing executives in dedicated areas for set time-frames, which would resemble more classic corporate governance structures (with plenty of room for hybrid, as well as newly imagined, forms).

Still one can separate codified decision-making authority and control over reward functions — the principals — on the one hand and the reward functions that govern the actions of agents on the other hand for analysis. The former are represented for example by native governance tokens that define network ownership, while the latter are for example token incentives for contributors or the distribution of earnings for analysis.

Control through cryptonetwork ownership

Tokenized on-chain governance means holders have voting rights. In order to steer a project’s or company’s governance towards optimizing for long-term success, tokens (ergo, voting power) must be distributed towards long-term oriented stakeholders.

It is those who have the strongest attachment to a given system (or skin in the game), which are most inclined to responsibly govern it.

Stakeholder lock-in is a measure of interest alignment and legitimacy of governance rights (see our prev. paper)

A great opportunity with programmable tokens is to design custom vesting structures that model each stakeholders’ time horizon of remaining with the protocol.

We have previously argued that all stakeholders should be represented in governance, which is a difficult, though worthwhile endeavor. One could focus on a broad and balanced distribution of transferable governance tokens amongst stakeholders, or utilize systems that also distribute voting power based on non-transferable reputation scores earned from valuable input to an organization (e.g. labor). Further, non-codified (real-world) reputation can be a strong measure of skin in the game.

“Community is about ownership — feeling not just that I am part of something bigger than myself, but that I have some skin in the game. It doesn’t matter so much whether that stake is economic or not — in fact, I think non-economic stake (e.g. reputation) can be a much bigger motivator.” Lane Rettig, former Ethereum core dev, currently part of Spacemesh.

Also, there are many projects where off-chain or informal governance prevails and has significant influence over a system.

This post further focuses on on-chain governance mechanisms through transferable tokens that represent financial value on secondary markets (financial capital backing a project).

The mechanisms discussed are however only single pieces in the toolkit among many, which can and will be iterated on (as well as applied in combination). After all, the best mechanisms cannot trump a strong community with cult-like culture.

Smart contracts allow for measuring and representing long-term commitments

One can define increases in voting power based on certain measurable commitments in a granularly programmable and easily verifiable fashion (e.g. a lock-up for a certain period of time).

- Committed long-term capital could have more voting power in order to optimize for long-term goals

- Profits could be distributed in a higher proportion towards committed long-term capital

Looking towards traditional corporate governance, tenure voting is often suggested in order to align long-term interests. To a large extent, rigid requirements of traditional large exchanges and regulators concerned about discriminating any class of shareholders over another in the US dominated financial system prevented large-scale adoption (see also a16z on that topic).

As opposed to traditional tenure voting, which is mainly backwards looking in terms of the time a given instrument (such as equity) has been held, crypto protocols specifically utilize forward looking mechanisms. This is a superior fit for optimizing long-term decision-making which by definition is about the future.

Incentivizing long-term commitment and decision making

On one hand, distributing control over an organization based on the strength of one’s locked capital should (1) attract long-run stakeholders and (2) automatically weight votes based on the strength of long-term alignment.

On the other hand, the question arises why someone would enter into such a lock-in in the first place, given the opportunity cost associated with giving up their liquidity? Is an increase in voting power reason enough? How should rewards, if any, be structured for stakeholders?

One interesting approach is to grant additional advantages in the form of boosted token rewards (a multiplier of rewards that are paid to contributors) and to distribute residual profits based on the length of the lock-up. Intuitively this makes sense: Long-term committed capital is more valuable (and on the other side of the coin more costly) than short-term committed capital. In debt markets, there are usually higher yields being paid for longer duration bonds than shorter duration.

Token holders as both principal and agent

As argued previously, stakeholder relationships and roles in DAOs overlap to a larger extent than in traditional firms. One lens through which to view a DAO is as a worker-owned cooperative (see our prev. governance paper or leadership in cryptonetworks). Many DAOs operate to a large extent through directly voting on proposals. Token-holders both have the authority of decision-making over the direction of the whole organization (principal), while finding themselves in more executive roles as developers or other contributors (agents). Monitoring functions are performed to a larger degree in a p2p manner, enabled through a high degree of transparency based on the shared ledger and other commons such as forums and openly accessible community chats (Discord).

In the context of traditional companies, it has been found that long-term executive incentives indeed have led to improved long-term performance (including improved innovation and social responsibility).

Viewing token-holders in their role as directly democratic executive decision-makers, one could argue that they need to be compensated with long-term incentives. One such incentive design can be allocating profits based on the length of a capital lock-up. As a result, even if there is compensation flowing to them at present, a certain level of skin in the game is enforced through the mechanism.

Arguably, the structures of DAOs will still evolve and become even more multifaceted than today with increasing representation and to some degree specialized executives (be it protocol politicians with delegated votes or novel structures that allow executive power at the edges of an organization).

Thus, there is room for specialized forms of incentive designs for individual functions within an organization. To highlight one interesting mechanism, KPI options allocate rewards based on reaching certain performance metrics — be it as a collective or targeted at individual roles.

This post continues elaborating on some of the challenges with time-lock weighted token voting, while the longer-form paper goes into more detail explaining the mechanisms, looking at case studies of Curve, including its relationship with aggregators such as yearn and Sovryn.

Challenges

Hedging exposure can create misaligned incentives

If stakers of a governance token that receive a boost in both voting power and rewards can hedge their exposure through some mechanism, they could achieve increased influence over a protocol, while not being economically aligned to the full extent of their tokens locked.

Two mechanisms that achieve this are smart-contracts that allow tokens to be made liquid through tokenization (allowing holders to sell their tokenized position), as well as external lending and derivatives markets.

The challenges mainly arise in a pseudonymous setting, as is often desired in cryptoeconomic systems and communities in order to promote privacy and resilience. An identity solution that reliably ties a given on-chain address to a specific user would align that person with the organization quite well. Hedging one’s exposure can and is in many cases constrained through traditional natural language contracts, however where not possible or desirable, alternative remedies have to be found.

Staking with smart contracts can create liquidity and vote delegation

As exemplified by the yearn yveCRV vaults and alternatives (see the full paper for a deep dive), smart contracts that time-lock tokens can, in turn, make the position liquid by tokenizing it, while allowing different classes of stakeholders (CRV holders & LPs) to share in the rewards that otherwise would need to be earned by stakeholders having both CRV and LP positions. In the case of yearn, StakeDAO as well as convex.finance, voting power of individual users that use the mechanism is effectively delegated to the aggregator communities as a whole.

The effects of the delegation depend on the way governance decisions are taken in those particular communities. The relationships could well be symbiotic, allowing all communities to thrive to a greater extent than each of them individually. Alternatively, a community that amasses excessive governance power in another could exploit their power. This highlights the necessity of whitelisting smart contracts in order to control the ability of token holders to behave in undesired ways.

Potentially, certain smart contracts could be whitelisted with a limit on the total number of tokens to be locked, in order to define the maximum influence an external DAO can have on the governance of the project in question.

Lending & derivatives markets

External lending and derivatives markets allow holders of locked tokens to hedge their exposure by short-selling the token in question. As opposed to smart contracts that make a given position liquid through tokenization, voters can sell a greater amount than 100% of their value locked, which could potentially open the door for malicious governance attacks. In such a scenario, an actor would lock-up his tokens to gain governance power, while entering into a highly leveraged short position on an external market. If the actor has a governance stake significant enough to influence the outcome of particular proposals, he can maliciously try to decrease the value of the network in question and profit through the highly leveraged position in the opposite direction.

However, this is not a problem particular to time-commitment scaled voting. On the contrary, such mechanisms alleviate the attack surface due to the fact that, depending on parameters, a short position would need to be upheld for extended periods of time (potentially on the order of years). The longer the time-frame, the longer the expected cost as well as uncertainty of cost and price-movements of the token in question, which in turn makes exploits both less profitable as well as considerably more risky, which should serve as strong deterrents.

A particular subset of this attack utilizes flash-loans in order to exploit a voting mechanism. In such an attack, tokens are lent out, a governance vote is affected and the loan is paid back in the same block (see e.g. a case in MakerDAO). By scaling voting power based on the time-lock, flash-loans would be made maximally ineffective, as the tokens could not be locked for any time-period in order for them to be paid back within a single block.

Beyond malicious behavior, hedging can enable stakeholders to reap the benefits of increased voting power as well as rewards, while being less economically aligned with the success of the project. As a result, they might place less diligence in their governance actions than they would have otherwise. A factor alleviating this is the incentive to time-lock governance tokens in the first place. If staking rewards are high enough, the supply available on lending markets will be very limited, which makes shorting prohibitively expensive to offset exposure over long periods of time. If synthetic derivatives exist, their pricing will likely also be affected by similar dynamics, as longs will take into account the increased rewards they could earn through participating in the staking mechanism, which in turn makes shorts more expensive (in e.g. perpetual swap contracts).

Physically exchanging keys to exit positions & early exit fees

Even if time-locking of tokens is properly governed on-chain to avoid undesired work-arounds (e.g. through a well executed smart contract whitelisting policy), the private keys that control access to voting rights can be exchanged physically in pseudonymous systems that do not require identification of users. As a result, a time-commitment can be transferred from one person to another without any strings attached.

This opens up the question of whether it is important to reward specific personas or ownership positions irrespective of their ultimate beneficial owner with increased voting power and rewards? How would the behavior of a given voter change based on the possibility to trade private keys in a pseudonymous system?

As exemplified in the case of Sovryn there is the possibility to withdraw time-committed tokens earlier by paying a penalty fee. It is likely that private keys to a given staked position would also trade at a discount, depending on the length of time they are still locked up for, as they lack the optionality of unlocked tokens. However, buyers of such positions might want to stake them anyways in order to enjoy the benefits, which would lead to a lower discount compared to the penalty fee. If the mechanism employed in a community explicitly employs a penalty fee that is re-distributed to loyal stakers, the social contract of such a community would likely deem such behavior as socially harmful and thus undesirable.

The behavior change of the voter in governance should depend on the expected discount at which she can dispose of the staked position in the short-to-medium term, similar to how a penalty fee would affect such behavior. If staked tokens can be disposed of relatively cheaply (close to their principal value), there is a relatively stronger incentive to boost voting power to drive short-term oriented outcomes, at the detriment of the long-term, to then exit positions before the long-term plays out. With an on-chain mechanism that explicitly defines penalty fees for early exit, the payoff structures of such behavior can be controlled to some extent, while re-distributing some of the gains of short-term activists to long-term stakeholders.

In order to avoid the work-around through exchanging private keys of staked positions, such behavior should be made as costly and infeasible as possible. Though, it should already be much more difficult and costly to find a willing counterparty for such a trade, as opposed to regular token markets (due to difficulties in execution, potential counterparty risk and much lower frequency of such trades).

A community could leverage social norms to explicitly deem exiting time-committed positions without complying to the penalty fees of the on-chain mechanism as undesirable and define steep slashing penalties for actors that are found to have engaged in such behavior (through majority governance vote). It remains to be seen, however, to what extent such behavior can be observed. At least though, the threat of slashing would make it much more difficult to find willing counterparties, as openly announcing the willingness to trade one’s time-locked tokens could be deemed a slashing condition already, which thus makes it much more costly and infeasible to execute.

Concentration of token holdings through compounding

Heavily rewarding long-term committed token holders could allow the most dedicated ones to accumulate increasing amounts of the total supply, countering the ideals of decentralized ownership and control. Potential remedies include combining token-weighted voting with other measures of skin in the game such as reputation and allowing motivated contributors to earn themselves a meaningful stake. Another potential remedy is to leverage quadratic voting on the basis of identities so that several individuals with a given stake have a higher weight than a single individual as an equalizing force (though this is still a hard problem to solve in a decentralized fashion).

Attracting and maintaining good governors

Finally, the governance outcome of any mechanism heavily depends on the composition of participants. While long-term oriented mechanisms should attract long-term oriented community members, it is not a given that they have the necessary knowledge or skills to responsibly govern a given system.

In order to be sustainably successful,it is crucial for projects to attract as well as educate the community and team members that are fit for the specific purpose, as well as align them with the organization’s core values. As described in the previously mentioned work by Jim Collins it is crucial to maintain a cult-like culture that preserves the core of an organization (mission/ideology), while at the same time stimulating progress through ambitious goals, experimentation and continuous improvement. Ideally, members organically grow within the organization/community into roles with increasing responsibility and governance power.

Conclusion

Projects that optimize for the long-term are considerably more successful in the long-run than those that do not. Thus, it is highly desirable to (1) implement governance mechanisms that serve that goal and (2) attract a community of stakeholders that aligns with such goals.

Time-commitment based distribution of governance power as well as rewards can be a powerful mechanism in that regard, due to the following effects:

- Rewarding long-term oriented over short-term oriented stakeholders should attract the former in the first place, while enticing them to time-commit

- Long-term alignment due to locked-in governance tokens should make stakeholders consider long-term value creation & accrual in the way they behave and vote

- Stakeholders that contribute specific types of resources — such as liquidity providers (LPs) who have decided to lock-up tokens in order to enjoy increased rewards — are inclined to make use of those benefits and thus incentivize them to become long-term providers of those resources, which allows for better planning for a given project

- Dynamic early exit fees can decrease the barrier to lock tokens in the first place and allow some level of short-term activism while partly re-distributing gains to loyal long-term stakeholders

While there are a number of challenges with such mechanisms — mainly centered around hedging economic alignment as well as applying work-arounds of the on-chain mechanisms — there are also potential remedies, which have been discussed.

Design decisions include (but are not limited to):

- Linear vs. progressive increase in governance power and rewards

- Types of rewards that are boosted through lock-up (e.g. protocol fee distributions, LP rewards)

- Minimum and maximum length of the lock-up

- Early exit fees

- Whitelisted smart contracts to participate in governance (and policy on how to whitelist)

- Social norms around slashing for actors that attempt work-arounds

As the space is still in its nascent stages and the mechanisms are supposed to lead to long-term success, it is too early to judge their effectiveness as of now on an empirical basis. It will be exciting to see further iterations of such approaches and their effectiveness in the wild over time.

If you are working on similar mechanisms, others that aim at the same goals, or have any feedback I would love to hear from you!

Many thanks to Mario Laul, Jack du Rose, Dermot O`Riordan, Pat Rawson, Lito Coen, John Light, Romain Figuereo and Evan Mair as well as my colleagues Jendrik, Georg and Gleb for their valuable feedback and discussions!

Disclosure: This content is for general informational purposes only that expresses our opinion, and it should not be construed as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice. Nothing contained here constitutes a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer by Greenfield One or the author to buy or sell any digital assets or other financial instruments. Greenfield One or the author may hold assets mentioned in the content. All data used is derived from publicly available sources.